China has the capacity to produce more than it does, that this is not new, but that this time it applies to a wide range of sectors. Each solution to this imbalance has its drawbacks: boosting domestic markets, but Chinese consumers lack confidence; improving quality, but it is already high; exporting, but tariffs are increasing... and not only in the US. These difficulties call for greater Chinese investment worldwide.

China has long accustomed to an investment-driven growth model, which is central to its stellar economic growth over the past three decades. But it also makes the economy susceptible to supply-demand imbalances, leading to recurring episodes of industrial overcapacity. These can be traced back to the 1990s, when accelerated market reforms led to a glut of labor-intensive manufactured goods. A more recent episode occurred in 2014-2016, when the massive investment-led stimulus that followed the global financial crisis triggered an oversupply of construction materials.

During the Coface Country Risk Conference last February, we asked Agatha Kratz about the impact of industrial overcapacity on China:

A growth model that has reached its limits

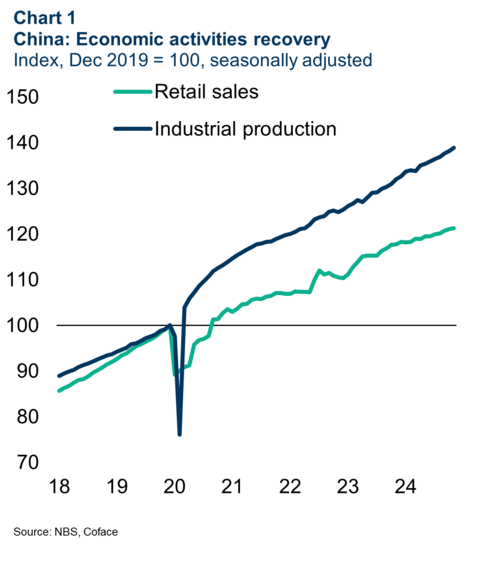

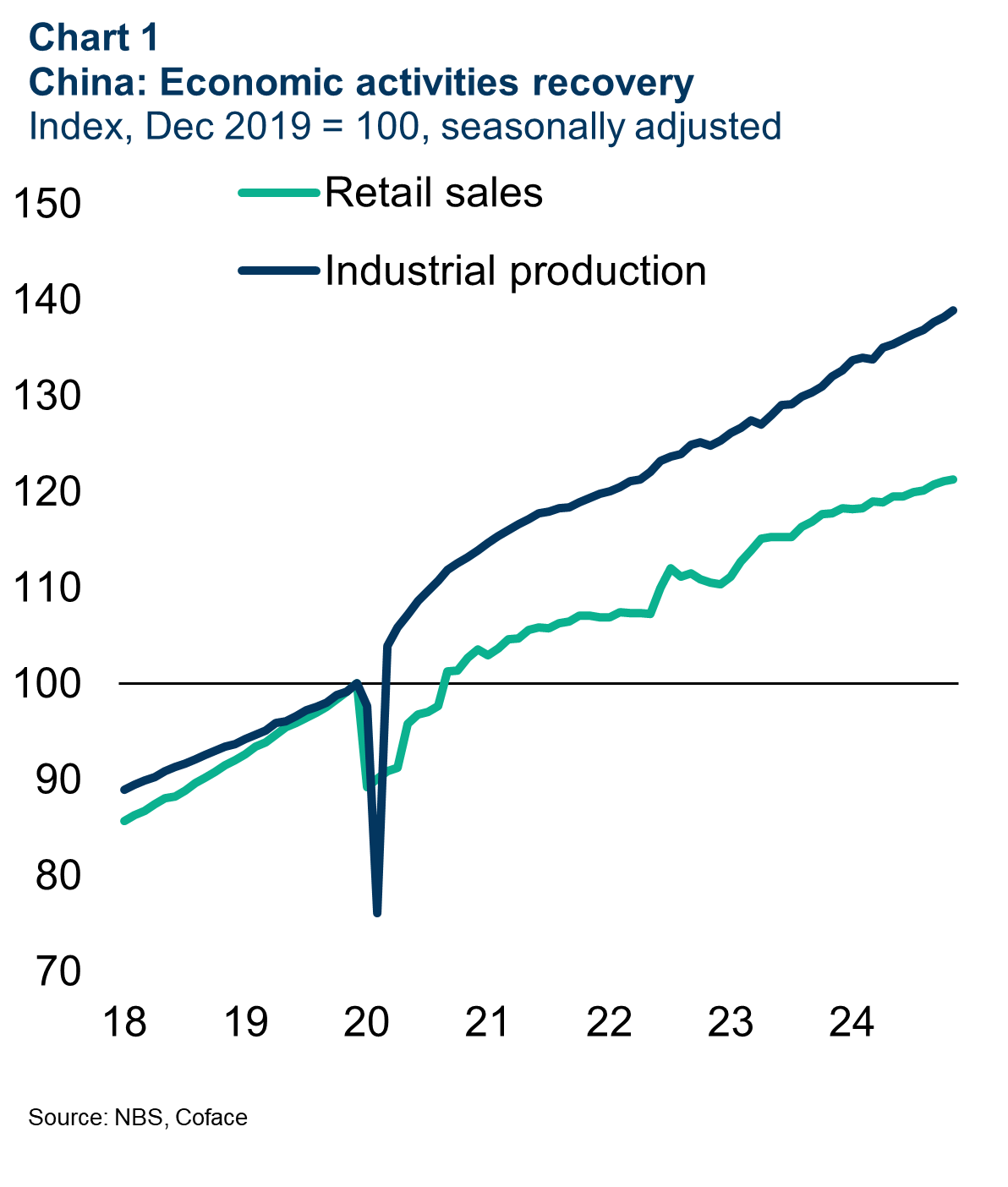

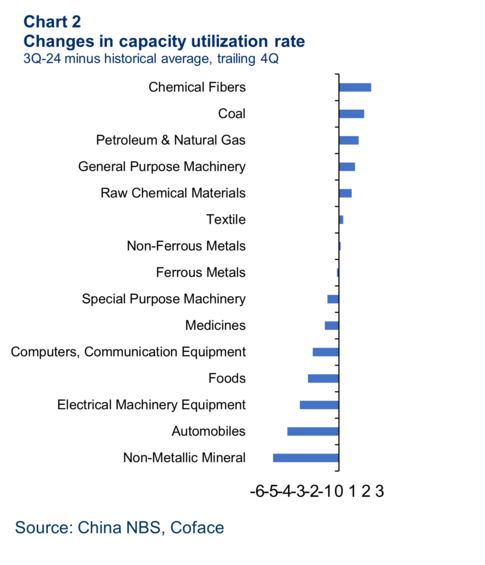

While this playbook is not new, the imbalances have become evident again since the COVID-19 outbreak (Chart 1), largely due to a production-driven stimulus approach aimed at reducing social interaction. Meanwhile, to pick up the slack from the shrinking housing market, the government has also proactively cultivated new growth drivers such as advanced manufacturing and green technology through state support.

Data for the graphs in .xls format

Overproduction with global consequences

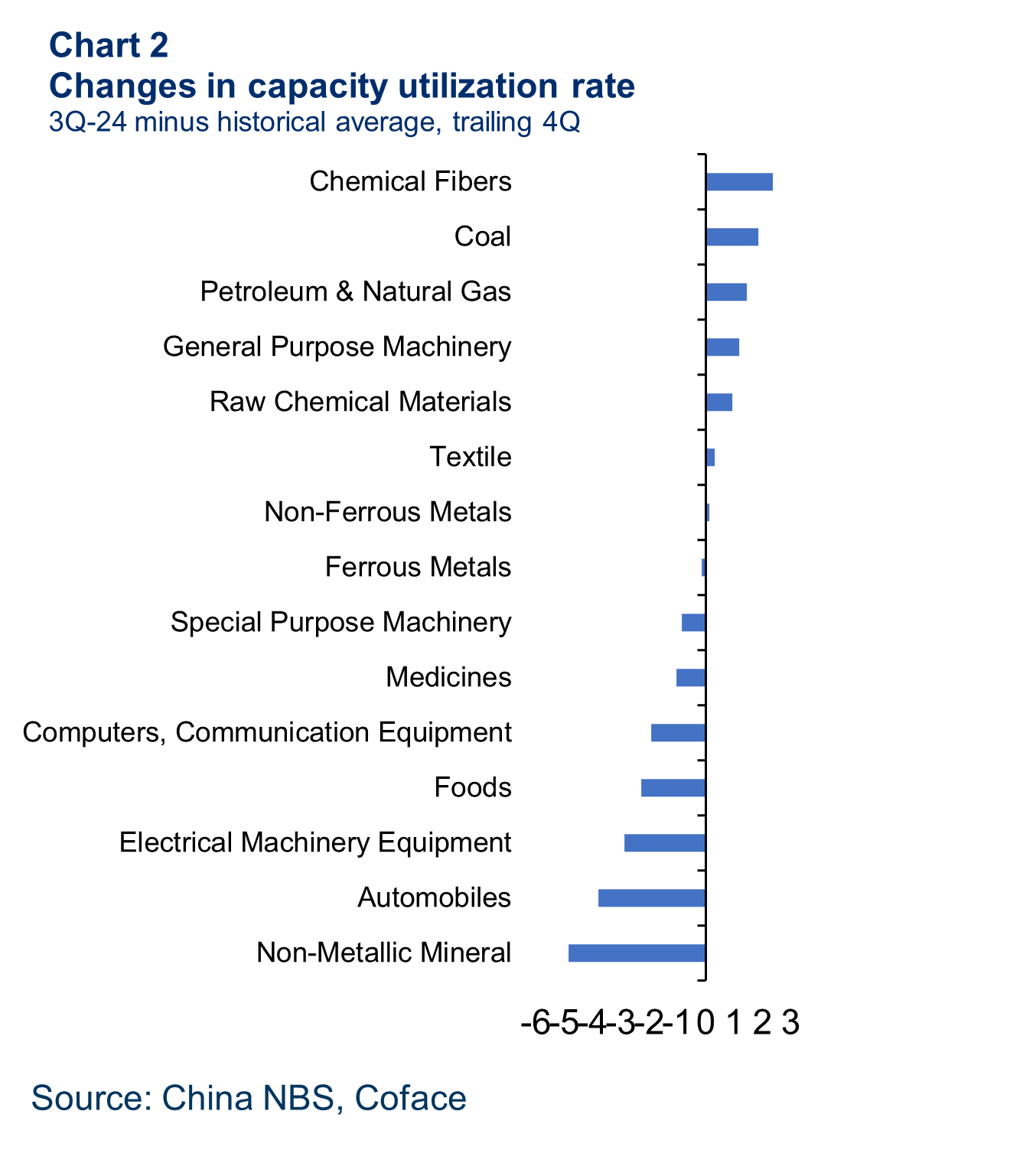

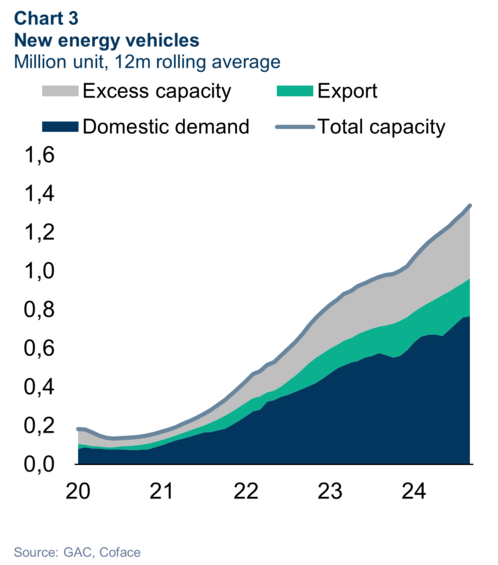

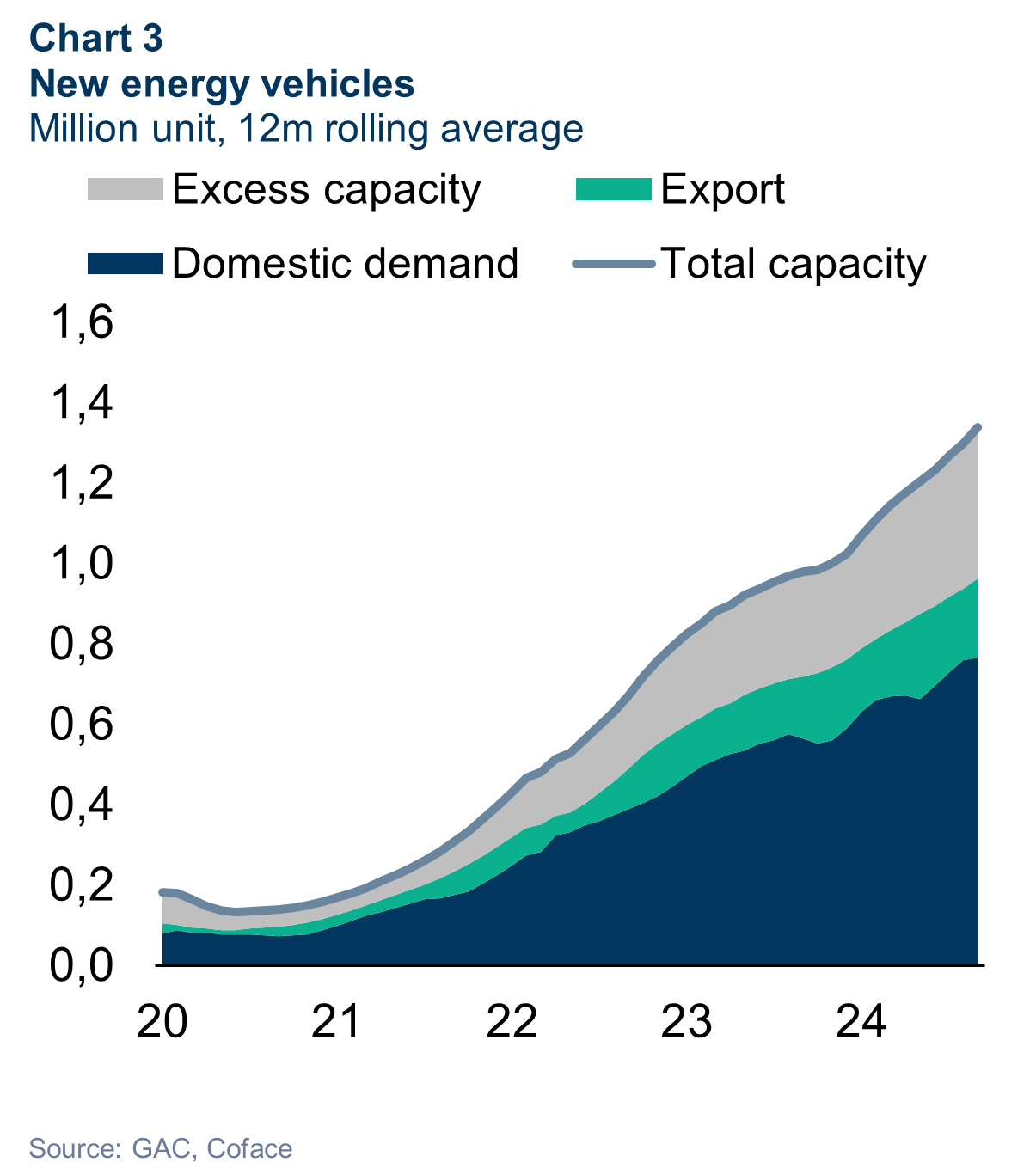

While the situation is not yet as severe as in 2016, overcapacity is prevalent in more sectors and faces more global pushbacks this time. It is no longer confined to specific sectors (labor-intensive consumer goods such as such as textile and home appliances in late 1990s, and construction materials such as steel and aluminum in the 2010s). This time, it has spread across traditional and emerging sectors. We see idle capacity most evident in consumer goods (food, medicine), construction non-metallic minerals (cement, glass), and machinery and transportation equipment (automobiles) (Chart 2). Our estimates show there is enough excess capacity in China to potentially double the exports of new energy vehicles and lithium batteries (Chart 3). But amid the global race of green transition, China’s production surplus in clean technology products has also made this round of overcapacity a focal topic globally and triggered more retaliations from trading partners.

Data for the graphs in .xls format

What solution to the Chinese overcapacity?

The most obvious solution to absorb excess production capacity is to expand domestic demand. Amid the ongoing supply-demand imbalance, recent policy focuses have shifted more towards subsidizing goods and facility consumption rather than construction. Meanwhile, efforts to stabilize the housing market have been made to curb the drag on household wealth given the substantial role of real estate in household assets. The ongoing buyback program for social housing supply is also the right move to disincentive the “saving for housing” motive, while access to affordable public housing can reduce rental burdens to unleash more spending power. But with consumer confidence near historic lows, the economy cannot just rely on demand-side recovery and endure chronic overcapacity. Because this will amplify deflationary pressures, affect corporate profits and hinder business expansion.

Government measures have also been taken to regulate capacity expansion through industrial upgrading. To this end, higher quality requirements have been imposed on the production of lithium-ion batteries, solar energy and cement clinker. These measures should help facilitate the orderly exit of excess capacity but are unlikely to be replicated across a wide range of industries. This is because doing so will harm short-term economic growth and would also be less technically feasible for advanced technology products with already high standards.

Historically, the shortfall in domestic demand has been compensated by external demand through exports. But now, Chinese exporters must navigate a more complex global trade environment as free trade is longer the hype it used to be. Trade barriers are already rising as developed economies aim to reduce their dependence on Chinese goods, likely even more so during a second Trump presidency. Against this backdrop, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a central component of Xi's "Major Country Diplomacy", can be instrumental in securing market access to the emerging world. But trade barriers erected by emerging economies have not abated either, as policymakers face pressure to protect domestic jobs and manufacturers.

Investment abroad, an unavoidable solution?

The increased trade frictions may in turn facilitate more outbound investment by China to bypass such barriers. In our view, this is the most feasible solution because overseas production bolsters intermediate goods exports but avoids trade frictions by bringing in jobs and technologies. Overtime, the industrialization in host countries could generate demand to absorb the excess capacity while helping to build new trade blocks for China with potentially less trade barriers.

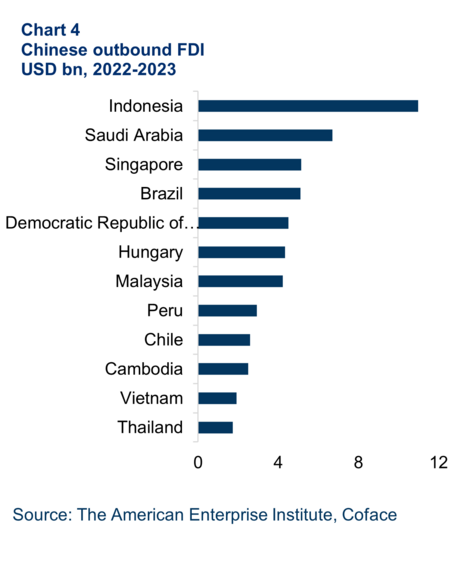

Some actions in this direction are already underway. Balance of payments statistics show that China has experienced a persistent outflow of direct investment since the second half of 2022, signaling a shift in China's role from a net importer of capital to an exporter. ASEAN remains the main destination for Chinese investment in 2022-2023, while Hungary is the main beneficiary in Europe, receiving 4.5% of Chinese FDI (Chart 4). Nevertheless, Chinese investment is coming under increasing scrutiny from governments in developed countries, not least for reasons of national security. In Europe, although scrutiny has intensified, some countries such as Hungary, Poland and Italy continue to welcome such investment, particularly in the electric vehicle sector.

Data for the graphs in .xls format

Domestically, there may be greater pressure to make up for job losses from increased outbound investment. This is especially true at a time of rising youth unemployment and weaker economic growth. To address this, the Chinese government has been working to further open up service industries (Internet, education, culture, telecommunications, health care), which tend to employ more workers and create more jobs. But there are uncertainties about its effectiveness, as investors still need to be assured of a more transparent and stable policy environment.

Want to dig deeper on Fragmentation of Trade?

Download our Guide on the Future of Global Trade